Impacts of the One Big Beautiful Bill Act: A Financial Planner’s Perspective

“Change is the law of life. And those who only look to the past and present are certain to miss the future.”

President John F. Kennedy

Executive Summary:

The One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBBA), signed into law in July 2025, enacts sweeping changes to U.S. tax laws with far-reaching implications for individual finances and estate planning. From a financial planner’s perspective, the Act brings permanent extensions of prior tax cuts, new deductions, and higher exemptions that especially benefit high-net-worth (HNW) and ultra-high-net-worth (UHNW) individuals.

Key provisions include making the 2017 tax cuts permanent (keeping top income tax rates at 37% instead of reverting to 39.6% after 2025), nearly doubling the federal estate and gift tax exemption to $15 million per person in 2026 (instead of dropping back to ~$7 million), and raising the state and local tax (SALT) deduction cap from $10,000 to $40,000 through 2029.

Households earning under $500,000 annually gain increased access to deductions and credits (e.g. a higher SALT write-off, an expanded child tax credit, and temporary deductions for seniors, tips, and overtime pay), whereas those above $500,000 see more mixed effects; they enjoy the continuation of lower tax rates and a larger estate tax shield, but face limits like a phase-down of the SALT deduction and new caps on itemized deductions according the Journal of Accountancy.

This report provides an in-depth commentary on OBBBA’s major changes from income tax brackets and deductions to estate planning and business tax incentives using graphics and examples to illustrate how the new law will impact households above and below the $500k income level.

Practical planning considerations (such as leveraging grantor vs. non-grantor trusts under the new rules and strategies for Qualified Small Business Stock (QSBS) gains) are highlighted to help individuals and families maximize benefits and prepare for the future.

While the Act offers substantial tax relief and clarity in many areas, it is important to remember that “permanent” tax laws can change with future legislation. Prudent planning including trust updates, gifting strategies, and income timing remains crucial, especially for families aiming to lock in these advantages amid an evolving fiscal landscape.

Key Tax Changes for Individuals

Income Tax Rates and Brackets: OBBBA cements the individual income tax rate structure established by the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) as a permanent fixture beyond 2025. This means the seven tax brackets (10%, 12%, 22%, 24%, 32%, 35%, 37%) stay in place instead of reverting to higher pre-2018 rates. For example, the top marginal rate remains 37% for high earners (which under prior law would have bounced back to 39.6% in 2026). Bracket thresholds also remain at TCJA levels, with an additional inflation adjustment for 2025 to ease the transition. The continuation of lower rates particularly benefits higher-income taxpayers by avoiding a tax hike; HNW individuals can plan with certainty that their ordinary income, bonuses, or capital gains (which continue to be taxed at favorable 0/15/20% rates for long-term gains) will not face an automatic rate increase in 2026. This permanency provides opportunities for strategies like Roth IRA conversions or accelerating income; actions that might have been deferred or taxed more heavily if rates had risen. Middle-income taxpayers also retain the TCJA tax cuts, though these were already built into current law through 2025.

Standard Deduction and Itemized Deductions:

The Act permanently preserves the doubled standard deduction from the TCJA, ensuring that the baseline deduction stays at $15,750 for single filers and $31,500 for married joint filers for 2025 (slightly higher than 2024 due to inflation) and continues to adjust with inflation thereafter. By keeping the standard deduction high and personal exemptions at $0 (they remain repealed), OBBBA continues the trend of simplifying filing for many taxpayers. However, for those who do itemize (often higher income with larger deductible expenses), new limits have been introduced that will especially affect top earners.

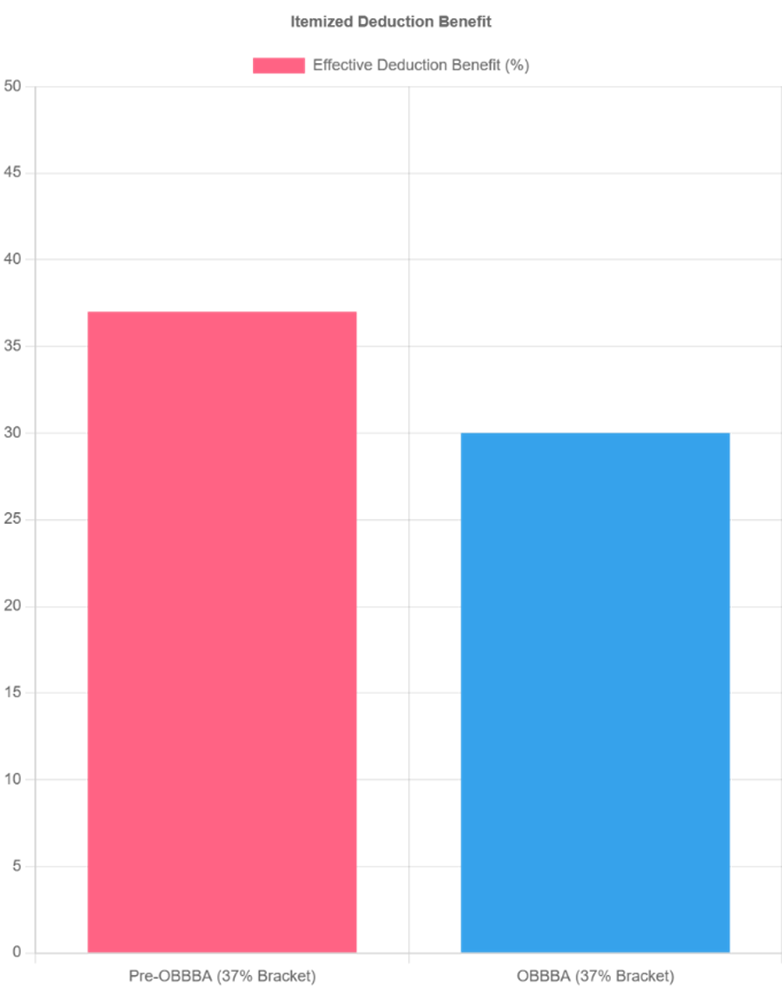

Notably, the law imposes a cap on total itemized deductions for the highest bracket taxpayers: starting in 2026, itemized deductions are reduced by a formula targeting incomes in the top 37% bracket. In effect, this rule trims the value of all itemized deductions by about 2 percentage points for top bracket taxpayers (a $100 deduction yields at most ~$35 tax savings instead of $37 at the 37% rate). This overall limitation considered a new kind of “Pease” provision means that individuals will get slightly less benefit from deductions like mortgage interest, charitable contributions, and SALT compared to before. Additionally, the Act makes TCJA’s elimination of miscellaneous itemized deductions permanent (expenses such as unreimbursed employee costs or investment advisory fees remain non-deductible). One small tweak is that unreimbursed educator expenses, previously slated to return, are now explicitly disallowed as miscellaneous deductions as well.

The deduction for mortgage interest on home loans remains capped at debt up to $750,000 (rather than rising back to $1 million) and interest on home equity loans continues not to be deductible, solidifying the more restrictive TCJA rules permanently.

Charitable contribution deductions see a significant policy change: beginning in 2026, itemizers can only deduct charitable gifts to the extent they exceed 0.5% of the taxpayer’s income (contribution base). This creates a sort of “floor” on charitable deductions, presumably to discourage very small charitable claims and simplify tax administration. At the same time, the law retains the higher 60% of AGI limit for cash gifts to public charities (instead of dropping to 50%), and introduces an above-the-line charitable deduction up to $1,000 (single) or $2,000 (married) for those who do not itemize. In practice, high-income philanthropists may need to “bunch” donations into certain years to overcome the 0.5% threshold and maximize deductions. Tools like donor-advised funds can facilitate this strategy by allowing a big deductible donation in one year while granting to charities over time. Meanwhile, low- and middle-income taxpayers who take the standard deduction get a small bonus deduction for charitable giving (up to $1k/$2k) to reward their donations even without itemizing. Overall, these deduction provisions somewhat limit tax benefits (via the itemized cap and charitable floor) while giving modest new benefits to non-itemizers, indicating a policy intent to target relief to middle-income families and prevent very high earners from leveraging excessive deductions.

State and Local Tax (SALT) Deduction Cap:

The treatment of the SALT deduction which has been a major point of contention since 2018 is substantially revised in the short term. Under TCJA, individuals could deduct a maximum of $10,000 in combined state income and local property taxes, a cap that was set to expire after 2025 (potentially restoring unlimited SALT deductions). OBBBA temporarily raises the SALT cap to $40,000 per return (for both single and joint filers) starting in 2025. This higher cap will be indexed for inflation from 2026 through 2029 (e.g. it becomes $40,400 in 2026)[1]. However, not all taxpayers will get the full $40k deduction.

The law includes an income-based phase-down: for households with modified adjusted gross income (MAGI) over $500,000, the allowable SALT deduction is gradually reduced as income rises, though it can never drop below the baseline $10k. In practical terms, a married couple earning just under $500k can utilize the full $40k SALT write-off (if they have that much in state/local taxes paid), but a couple earning substantially more will see their benefit curtailed. The phase-out rate is 30% of income above $500k, meaning that by about $600k of MAGI, the effective cap shrinks back to $10k. High-income residents of high-tax states therefore get only limited relief: for example, someone with $550k MAGI might be able to deduct around $25k of SALT instead of $40k, and extremely high earners (>$600k) are essentially stuck with the same $10k cap as before. After 2029, the SALT cap is scheduled to revert to $10,000 permanently (OBBBA does not extend the $40k cap beyond 2029). The temporary nature of this change suggests it was likely a compromise: it offers near-term relief to upper-middle-income taxpayers in states like NY, NJ, CA, but it doesn’t give a permanent, full break (who had lobbied for repealing the cap entirely).

Figure: Maximum SALT deduction allowed under OBBBA for 2025, by household income. For incomes up to $500,000, taxpayers can deduct up to $40,000 of state and local taxes. Above $500k, the SALT deduction limit is phased down by 30% of the excess income, reaching the minimum $10,000 cap once income hits $600,000 (and remaining at $10k for any higher incomes). This phase-down blunts the benefit of the higher SALT cap for very high earners, while still providing substantial relief to those in the $100k–$500k range who often faced the full $10k cap under prior law. Notably, these figures apply per tax return; they are not doubled for joint filers (the $40k cap is the same for singles and couples).

From a planning perspective, the SALT changes open some opportunities for strategy. Individuals under the $500k income threshold can plan to accelerate or bunch deductible tax payments (such as property taxes) into years 2025–2029 to fully utilize the temporary $40k cap. In contrast, higher earners (>$500k) should be aware that their federal benefit from SALT payments will still be largely capped at $10k–$20k, so they might consider alternative tactics like charitable contributions or other deductions for tax mitigation.

The good news is that OBBBA did not include earlier proposals to clamp down on SALT cap workarounds using pass-through entities. Many states have enacted Pass-Through Entity Taxes (PTET), which effectively allow S-corporations or partnerships to pay state income tax at the entity level (thus generating a fully deductible business expense that flows through to the owners) instead of the owners paying individually and being subject to the SALT cap.

This means high-income professionals and business owners can continue to utilize state pass-through tax elections to circumvent the federal SALT cap, preserving those state tax deductions above $10k at the entity level.

Trust planning is another consideration: because the SALT cap applies per tax filing, establishing multiple non-grantor trusts (each of which is a separate taxpayer) may allow a family to multiply the number of $10k (or $40k) SALT deductions they can use. With OBBBA’s changes, trustees of existing non-grantor trusts might choose to retain more income within the trust (instead of distributing it) to use the trust’s own SALT deduction capacity.

Conversely, individuals with grantor trusts (where the grantor pays the trust’s tax) might evaluate the benefit of “turning off” grantor status – effectively converting to a non-grantor trust – so that the trust can deduct state taxes on its return. This has to be weighed against the many benefits of grantor trusts (like allowing the grantor to pay income tax as an additional gift to the trust). In summary, the higher SALT cap is a boon to many upper-middle-income households in high-tax locales, but for the wealthiest, its phasedown and eventual sunset mean it’s not a game-changer. They will continue to rely on techniques like PTET elections and trust structuring to manage SALT limitations.

Tax Credits and Special Deductions: The Act also introduces or extends several tax credits and niche deductions that can impact personal financial planning. For families, the Child Tax Credit (CTC) is enhanced – the maximum credit is increased from $2,000 to $2,200 per child starting in 2025, with future inflation indexing. The income phase-out thresholds for the CTC remain at $200k single / $400k joint, which were previously raised by TCJA and now made permanent. This change modestly benefits families with children, although the additional $200 is not a massive sum; it mostly keeps the credit value from slipping due to inflation. A more novel addition is the creation of so-called “Trump Accounts”, a nickname for a new tax-advantaged savings vehicle for children. These accounts allow parents to contribute for a child under 18 and later withdraw funds tax-free if used for specific purposes like education, first-time home buying, or starting a small business. Contributions are limited (the exact annual limit is relatively modest and was defined in the legislation), and the account must be fully distributed by the time the beneficiary reaches age 31. There’s also a one-time $1,000 bonus credit for accounts opened for children born between 2025–2028 to encourage early participation.

While these “Trump Accounts” provide another tool for college or down-payment savings, financial planners may still prefer the well-established 529 college savings plans, which OBBBA also liberalized further. The Act expands the allowable uses of 529 Plan funds, explicitly permitting 529 withdrawals for K–12 education expenses and vocational/trade programs (areas that were partially addressed by prior regulations and now broadened). It also raised contribution limits and made other technical tweaks to give 529 plans more flexibility, reinforcing them as a cornerstone for education funding.

Finally, for seniors, OBBBA provides a temporary benefit: a “Senior Deduction” of $6,000 for taxpayers aged 65 and older. This is available from 2025 through 2028 and is on top of the normal additional standard deduction (people 65+ already get an extra standard deduction of ~$1,850 single or $1,500 each if married). The new $6,000 senior deduction is not restricted to any specific use (it’s not like a medical deduction – it’s essentially just an increased write-off for seniors).

Importantly, it is phased out for higher-income seniors: the deduction starts to phase out once MAGI exceeds $75,000 for singles or $150,000 for couples, and it phases out completely by $175,000 single / $250,000 joint income. This means a retired couple with $300k income from pensions and investments would not get this deduction at all, whereas a senior couple with $100k income would get some benefit (perhaps the full $12k if both are over 65 and under the phase-out threshold). From a planning angle, middle-income retirees might consider timing of income (for example, being careful with large IRA withdrawals or capital gains) to keep MAGI below the phase-out, at least during 2025–2028, to enjoy this temporary $6k per person tax break. High-income seniors (including many HNW clients) will likely be phased out and thus unaffected.

It’s also separate from Social Security: despite some political commentary, OBBBA did not remove taxation on Social Security benefits (those remain taxable as under prior law). The senior deduction simply gives older taxpayers a bigger tax-free cushion, but it does not depend on receiving Social Security and it does not reduce adjusted gross income (it’s taken after AGI is computed, so it doesn’t help avoid Medicare IRMAA surcharges or other AGI-based thresholds).

In summary, households below about $500k income have opportunities to gain new tax benefits from OBBBA’s individual provisions: they keep a low tax rate, can deduct more SALT for a few years, get a bigger standard deduction and child credit, and might qualify for special breaks (senior, overtime, etc.).

The next section will look more directly at how these changes translate into overall impacts for different income groups.

Estate and Gift Tax Exemption Changes and Trust Planning

One of the most significant impacts of the Big Beautiful Bill for is in the realm of estate planning. The Act delivers on making the federal estate, gift, and generation-skipping transfer (GST) tax exemptions not only permanent but even larger than before. Under prior law, the estate/gift tax exemption was approximately $12.92 million per person in 2023 and expected to be around $13–$14 million in 2025 (after inflation adjustments), but then would have reverted to about $5–$7 million in 2026 (cut roughly in half) when the TCJA provisions expired. OBBBA prevents that cliff by setting the exemption at a flat $15 million per individual starting in 2026, indexed for inflation thereafter. For a married couple, this equates to a combined $30 million shelter that can pass free of estate or gift tax. The estate/gift tax rate remains 40% on amounts above the exemption, unchanged from prior law.

This change is monumental for larger estates: it essentially doubles the amount of wealth that can be transferred tax-free compared to what the law would have been. For example, without OBBBA, the exemption in 2026 would have snapped down to roughly $7 million. A $15 million estate might have incurred about $3.2 million in federal estate taxes (40% of the $8 million over the threshold). Under the new law, that same $15 million estate would owe $0 in federal estate tax. Even a $30 million estate (for a couple) would now be fully covered, whereas previously it would have faced taxes on roughly half its value.

It provides certainty and incentive for renewed estate planning: affluent individuals can confidently make gifts or set up trusts utilizing the full $15M exemption without fear of losing that benefit in 2026. In fact, families who rushed to use the higher exemption before 2025 (the “use it or lose it” scenario) may find they still have additional exemption available and can do more gifting. Those who didn’t use it now no longer face an immediate deadline, but should still consider acting while the political environment favors large exemptions.

We would advise our clients to revisit their estate plans in light of the new law.

For estates that now fall under the $15M cap, estate tax essentially becomes a non-issue at the federal level but state estate taxes might still apply. It’s important to note that a number of states have their own estate or inheritance taxes, often with much lower exemptions (e.g. $1M in Massachusetts, $5.25M in Illinois, etc.).

With the federal exemption so high, state estate taxes may become the primary death tax concern for certain clients. Some states could respond by reevaluating their estate tax regimes, and planners might increasingly incorporate strategies to mitigate state estate taxes (like gifting property out of state, using life insurance for liquidity, or even changing residency to a no-estate-tax state).

Trust and estate planning techniques remain largely intact under OBBBA. During debates in recent years, there were discussions of curbing popular tools like grantor trusts (which allow the trust’s income to be taxed to the grantor, effectively removing the tax burden from the trust and allowing it to grow faster) and GRATs (Grantor Retained Annuity Trusts), or imposing new rules like capital gains at death or a wealth tax. None of those restrictive measures made it into the final Act. The only major change was raising the exemption itself. This means techniques like Intentionally Defective Grantor Trusts (IDGTs), Dynasty Trusts, and GST planning are still on the table and arguably more powerful now.

For instance, a grantor can now fund an IDGT with $15 million worth of assets without incurring gift tax, and because it’s a grantor trust, the grantor will pay the income taxes on the trust’s earnings each year – effectively allowing an extra tax-free transfer to the trust (since the trust’s growth isn’t diminished by tax payments, and the grantor’s payment of the tax is not considered an additional gift).

With a higher exemption, grantors can shift even more assets into such trusts in 2026 and beyond, removing future appreciation from their estates. The preservation of grantor trust rules is critical – had those been altered, many estate freeze strategies would have been jeopardized. Planners should reassure clients that grantor trusts remain a cornerstone of advanced estate planning post-OBBBA, providing flexibility (through powers to substitute assets, for example) and tax efficiency (grantor pays tax).

At the same time, non-grantor trusts may gain renewed attention for income tax planning, as touched on earlier. Non-grantor trusts can claim their own $40k SALT deduction (subject to the cap) and can also take deductions for charitable contributions without being subject to the individual standard deduction limitations. For high-income families who are bumping against itemized deduction limits personally, it might make sense to channel some charitable giving through a non-grantor trust or family foundation entity, so that the trust can fully deduct the donations whereas the individuals might not get full benefit due to the 0.5% floor or itemized cap.

Additionally, with the GST exemption also at $15M per person (since GST tax exemption equals the estate tax exemption), families can allocate more to generation-skipping trusts to benefit grandchildren and further descendants without incurring transfer tax.

The OBBBA does not change GST tax rates or rules, so the focus remains on fully using that exemption. One strategy that becomes more viable: funding multiple “pot trusts” or dynasty trusts up to $15M each for children and grandchildren, possibly leveraging valuation discounts for interests in family businesses or real estate to stretch that $15M exemption even further in terms of real economic value transferred.

It’s also worth mentioning the step-up in basis at death remains untouched in this law. Assets passed through the estate still get a stepped-up cost basis for heirs, eliminating built-in capital gains. With more assets now escaping estate tax due to the higher exemption, the step-up becomes an even more valuable benefit. Clients holding appreciated stock or property can plan to let those assets transfer at death rather than selling during life, to wipe out capital gains for their heirs, without estate tax concern if under $15M. This reinforces strategies like “hold until step-up” for certain investments, balanced of course against the individual’s need for liquidity or diversification.

In practical advice, families near or over the $15M level should consider taking advantage of the exemptions soon. The political pendulum can swing and what one Congress enacts, another might scale back. Future budget pressures (the law does increase the deficit considerably) could prompt lawmakers to revisit estate taxes as a revenue source. As one estate planning commentary noted, “’Permanent’ means until Congress changes it” – so proactive planning is still essential. This may involve:

Making large lifetime gifts to use exemption (either outright to heirs or in trust) while it’s available,

Locking in valuation discounts by gifting minority interests in family entities,

Using tools like GRATs in low-interest-rate environments to shift future appreciation out of the estate,

Ensuring existing insurance trusts (ILITs), family partnerships, etc., are reviewed and aligned to the new law.

Additionally, updating old trust documents is wise. Some older trusts have formula clauses tied to “whatever the exemption is at death” – those could now fund trusts with much larger amounts than originally anticipated (given the jump to $15M) which might or might not be what the grantor intended. Techniques like trust decanting or adding trust protector powers can be used to adjust terms if needed to adapt to the new exemption landscape.

For example, if a bypass trust formula would leave $15M to children and only the remainder to a spouse, that might overly starve the spousal share now – families might want to revisit that formula. With larger sums passing tax-free, asset protection and management for heirs become more pressing; trusts should be scrutinized to ensure they provide appropriate control, protection from creditors or divorcing spouses, and alignment with the family’s values (e.g. incentives for education or philanthropy).

In summary, the Big Beautiful Bill Act is extremely favorable for wealth transfer planning. It preserves all the sophisticated trust strategies that estate attorneys have honed over the years. And it gives a (perhaps temporary) green light to push forward with significant gifts and trust funding.

Business Owners and Investors: Pass-Through Income, QSBS, and Other Changes

OBBBA also contains several provisions affecting business taxation that in turn impact personal financial planning for business owners and investors. Two of the most notable are the adjustments to the Qualified Business Income (QBI) deduction for pass-through entities and a major expansion of the Qualified Small Business Stock (QSBS) exclusion under Section 1202. Additionally, the Act addresses areas like depreciation, R&D expensing, and other business credits, which indirectly influence individual business owners’ strategies.

Pass-Through Business Income (QBI) Deduction (Section 199A):

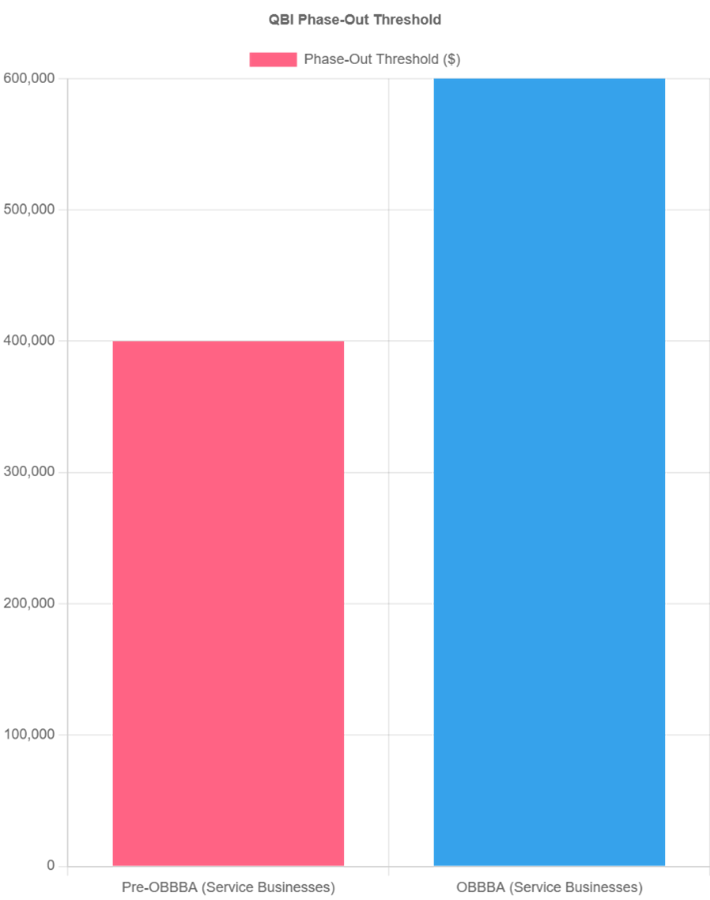

The QBI deduction, introduced in 2018, allows owners of sole proprietorships, partnerships, S-corps, and certain LLCs to deduct 20% of their qualified business income on their tax return, subject to various limitations. It was slated to expire after 2025, which would have effectively raised taxes on many small businesses and professionals by taxing all their business profits at full rates. OBBBA makes the 20% QBI deduction permanent going forward, removing the sunset provision. This offers long-term certainty. Business owners can count on this tax break not disappearing in 2026. The Act also modestly expands access to the deduction: it increases the income thresholds at which the deduction phases out for certain high-earning service professionals (like doctors, lawyers, consultants) and at which wage-and-capital limits kick in.

Under TCJA, for 2025 the phase-out for specified service trades or businesses (SSTBs) was around $440k joint income; OBBBA lifts these phase-out starting points by 50% (e.g. to about $150k for singles (from $100k) and $300k for joint filers (from $200k), with phase-outs extending correspondingly to ~$375k/$750k). This means some moderately high-income professionals who previously were cut off from QBI may now qualify for at least a partial deduction. The Act also adds a small minimum deduction of $400 for anyone with at least $1,000 of business income, which ensures even very small businesses get something.

For very high-income business owners (above the phase-out ranges), the deduction is still limited by W-2 wage and capital investment formulas, and SSTB owners above the limits still can’t take QBI at all. So a partner in a law firm earning $1M won’t magically get a QBI deduction now – they’re still excluded due to income – but a partner earning $300k might now qualify, whereas before they were partially phased out.

The planning implication:

Business owners should continue to optimize their operations to maximize the QBI deduction. With permanency, one can confidently make structural decisions (like staying as an S-corp vs converting to C-corp) knowing the 20% deduction will remain. Some strategies include adjusting salary vs. pass-through distributions (since too high an income can phase out the deduction, but also need sufficient wages for the wage limit if applicable), reviewing whether splitting a business into separate entities could isolate non-SSTB portions that qualify, etc. The slight raising of thresholds especially benefits owners of services businesses right around the old cutoff. They may consider income-smoothing techniques to stay under the new, higher thresholds and get the deduction.

On the other hand, incorporating as a C-corporation remains at a flat 21% corporate tax rate; OBBBA did not lower the corporate rate further, so pass-through vs. C-corp comparisons remain roughly as before. But by keeping QBI, the playing field stays more level for pass-throughs vs C-corps (one of TCJA’s goals was parity).

Qualified Small Business Stock (QSBS) – Section 1202 Exclusion: For entrepreneurial clients and investors in startups, OBBBA’s changes to QSBS are a game changer. QSBS refers to stock of certain C-corporations (with assets < $50M pre-investment, engaged in active business) held for over 5 years, which under pre-Act law allowed up to 100% exclusion of capital gains on sale (subject to a cap of $10 million in gains per issuer, per investor, or 10x basis if greater). This has been a tremendous tax benefit for founders and early investors in qualifying companies (like tech startups). The new law significantly expands these benefits:

It introduces a tiered exclusion schedule for QSBS sold before 5 years. Now, if stock is held at least 3 years, 50% of the gain is excluded; at 4 years, 75% is excluded; at 5+ years, 100% is excluded. Previously, you received no special break if you sold before 5 years (aside from older 50%/75% for stock acquired long ago). This change adds flexibility. Investors who need liquidity a bit earlier can still get a majority of the gain tax-free, which might encourage more investment in small businesses (since the “five-year cliff” is now softened to a ramp).

The bill raises the per-investor exclusion cap from $10 million to $15 million of gain per company, and this $15M will be inflation-indexed from 2027 onwards. This means successful investments can yield even greater tax-free rewards. For instance, if you invested early in a startup and your shares are now worth $20M gain, under old law you’d pay tax on $10M of that (above the $10M cap); under new law, you could exclude $15M – resulting in tax on only $5M of the gain. If you also had a very low cost basis, you still have the alternative of excluding 10 times your basis if that’s higher (that rule remains), but for many, the flat dollar cap is the limiter. Increasing it by 50% is a significant boon, especially for serial angel investors or venture funds. Moreover, if one uses estate planning creatively (for example, gifting shares to multiple non-grantor trusts or family members), each taxpayer entity potentially gets its own $15M cap – a strategy that becomes even more powerful now. Advisors will certainly consider spreading QSBS holdings among trusts for children or other vehicles to multiply the exclusions (while staying mindful of the gift tax implications and ensuring the trust or donee meets the 5-year hold requirement independently).

It increases the company eligibility threshold from $50 million in gross assets to $75 million, also inflation-indexed after 2026. This means companies can now raise more capital and grow larger while still being considered “small” for QSBS purposes. It broadens the universe of companies investors can target for QSBS treatment – some firms that would have tripped the $50M asset limit (perhaps after a big funding round) will still qualify up to $75M. This is very pro-startup and pro venture. It allows startups to scale further without cutting off QSBS for new investors. Founders can now be less cautious about taking additional investment that pushes assets over $50M; the threshold extension provides “headroom” for growth.

All these QSBS enhancements apply only to stock issued after the enactment date (July 4, 2025).

Stock acquired before that keeps the old rules (so an investor who already has QSBS from 2020 still has the $10M cap etc.). Therefore, there’s an interesting timing play: founders might want to close new investment rounds after July 2025 so that new shares get the better QSBS treatment. Individuals considering investing in a qualifying small business might likewise prefer to do so after enactment to secure the expanded benefits. It may also influence entity structuring. More businesses may be inclined to form as C-corps (to be QSBS-eligible) versus LLCs, given the tax-advantaged upside potential is now even larger.

QSBS can be integrated with estate planning, too. The law’s expansion of QSBS exclusion, combined with the higher gift tax exemption, suggests a strategy: fund nongrantor trusts with QSBS shares. Each trust that owns QSBS (if structured as a separate taxpayer) can claim its own up-to-$15M exclusion on gain. Affluent founders could transfer portions of their startup stock into multiple trusts for children or other beneficiaries.

After 5+ years (and assuming the company succeeds), each trust’s sale of QSBS could exclude potentially $15M of gain, multiplying the tax-free amount beyond what one person alone could do. This requires careful planning (ensuring trusts are indeed separate taxpayers and not merged for tax purposes by attribution rules) but is a known strategy that just became more potent. The higher GST exemption also means those QSBS-funding trusts can be generation-skipping, allowing potentially tax-free growth for multiple generations if the stock’s value appreciates aggressively.

Documentation and compliance for QSBS will be scrutinized.

The IRS is likely to pay more attention given the enlarged stakes. It’s crucial to keep records that the company met the active business requirement, the gross assets test, etc., and that the stock was newly issued for cash or services (QSBS must be original issuance, not bought/acquired secondhand). Founders and investors should work with tax advisors to ensure Section 1202 eligibility is preserved (for instance, avoiding certain redemption transactions that can jeapordize QSBS). Also note, QSBS is a federal provision as some states do not conform, so state taxes might still apply on those gains (ex. California taxes QSBS gains fully; others like New York follow federal).

Qualified Opportunity Zones (QOZ) and Rural Opportunity Fund Updates

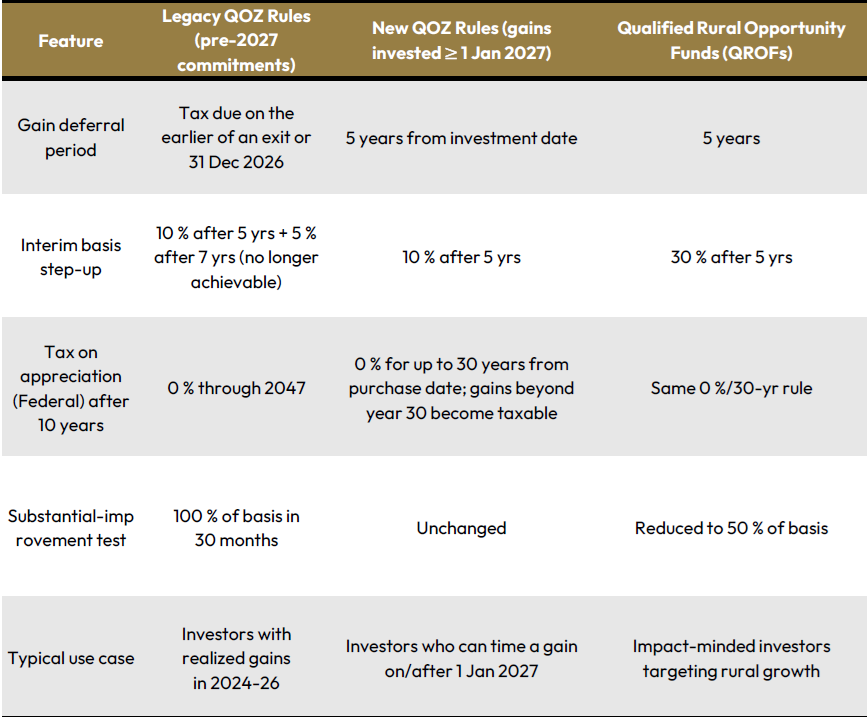

The One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBBA) modernizes the 2017‑era Opportunity Zone regime, creating two distinct tracks that investors will need to model separately in their planning models. A Qualified Opportunity Zone (QOZ) is a designated geographical area where investors can develop real estate projects in underserved communities with the opportunity to obtain significant tax advantages. QOZs are typically located in economically underprivileged communities across the United States. A Qualifiied Rural Opportunity Fund (QROF) is an opportunity zone specifically designated that offer enhanced tax benefits for investments in designated rural zones.

Below is a comparison chart reflecting the prior OZ rules with the new QOZ and QROF rules.

The practical implementation framework is important to be materially aware of going forward given the change and updates made to the law.

Time your capital gain.

If an investor is already sitting on a 2025‑26 gain, the legacy window still delivers full deferral through 2026 and, with a 10‑year hold, can permanently erase all federal capital gain appreciation. If one can control the realization date of the capital gain, deferring the sale until January 1, 2027 or later may be more attractive because of the ability to (i) defer tax for five years instead of paying in 2027, (ii) lock in a fresh 10 % basis bump at year 5, and (iii) enjoy tax‑free growth for up to three decades.

Segment portfolios.

Investors will need to track pre‑2027 and post‑2027 QOZ positions in separate sleeves; each sleeve has its own holding‑period clock, basis step‑up, and sunset date.

Leverage QROFs for rural alpha and a turbocharged basis bump.

The 30 % basis step‑up after five years effectively cushions downside risk and accelerates break‑even. The lower substantial‑improvement threshold (50 % of basis) opens the door to renovating older farm, fibre‑optic, or ag‑tech assets that would have been cost‑prohibitive under the urban rules.

Pair with complementary OBBBA tools.

There are opportunities to pair this legislation with other OBBBA strategies. One example would be to potentially consider funding QOZ/QROF contributions via grantor trusts while lifetime gift‑tax exemptions are at their new $15 million level to “freeze” further appreciation outside the estate.

Investor Due diligence still rules.

The deferral and exclusion mechanics do not fix a poor investment underwrite/deal. Leveraging qualified due diligence regarding sponsor experience, project underwriting, capital stack, and exit optionality, especially in thin rural markets where resale liquidity can be limited is important.

Bottom line:

OBBBA’s revamped QOZ framework re‑opens the programs best tax‑alpha window starting 2027, while the newly created Rural Opportunity Funds offer an even richer incentive set for investors willing to deploy capital beyond the typical urban corridors.

Beyond QSBS, QOZ and QBI, OBBBA contains other business-related changes that indirectly benefit many individuals:

Bonus Depreciation: The law makes 100% bonus depreciation (full expensing of qualifying capital assets in the first year) effectively permanent for assets placed in service after Jan 1, 2025. (Under prior law, bonus depreciation was phasing down from 100% to 80% in 2023 and further thereafter.) Now, a business owner can continue writing off equipment, machinery, certain qualified improvements, etc., immediately. This encourages investments and can reduce taxable business income (thereby possibly increasing QBI deduction too since QBI is after depreciation). For a small business owner, the ability to fully expense, say, a $200k machinery purchase in one year improves cash flow. Coupled with a higher Section 179 expensing limit – raised to $2.5 million with a phase-out starting at $4 million of asset purchases – even relatively large capital expenditures can be deducted upfront by small and mid-size businesses.

Research & Development (R&D) and other business incentives: Although not the focus of this report, the Act also addresses the treatment of R&D expenses.

OBBBA reportedly includes relief in this area, allowing more favorable write-offs for R&D and possibly enhancing R&D tax credits (a boon to tech and pharma startups). These changes help entrepreneurs by reducing after-tax cost of innovation.

Corporate and International Tax tweaks: For those individuals who own C-corp businesses or have interests in multinationals, OBBBA’s changes to international tax regimes (GILTI, FDII, etc.) might be relevant. The Act set up a new system (with new acronyms) but broadly, it prevented scheduled tax increases on foreign earnings from hitting in 2026. It slightly raised some rates on global intangible income but aimed to reduce double taxation. Family businesses with cross-border operations might benefit from the more stable and somewhat simplified international tax rules.

Green Energy Credits and Other Credits: The Act claws back a large portion of clean energy credits that were expanded in 2022’s Inflation Reduction Act. For instance, OBBBA repeals the tax credits for electric vehicles and residential solar after 2024, among others, and scales back others quicker. This means individuals considering buying an EV or doing energy-efficient home improvements should be aware that the federal incentives are being reduced. From a planning view, if one was eyeing an EV purchase, doing it before the credit disappears (if it hasn’t already) would be wise. Over a decade, the reduction of green credits raises revenue (about $500B saved by cutting these credits), but it could also alter investment decisions in clean energy projects.

Another niche area: the Act extends and expands certain provisions for 529 ABLE accounts (tax-advantaged accounts for individuals with disabilities), which could be relevant for families with special needs planning. Also, it tightens some rules for nonprofits (e.g. more nonprofits now subject to the 21% excise tax on very high executive pay over $1M, since it’s not just top-5 execs but all highly paid employees now), and it instituted a new tiered excise tax on large private college endowments to scrutinize their size. While these provisions don’t directly hit personal finances of most individuals, they might interest philanthropically inclined HNW clients (for instance, donating to large university endowments now has a slightly different context as those endowments face taxes at certain levels).

Conclusion and Future Outlook

The One Big Beautiful Bill Act represents one of the most consequential tax overhauls in recent history, with major implications for both affluent individuals and the broader economy. From a financial planning perspective, the Act provides a mix of opportunities and considerations:

Opportunities: High-net-worth persons stand to lock in historically low tax rates and generous exemptions. There is now a clearer runway for strategies like Roth conversions, tax gain harvesting (since rates are stable), and bracket management without fear of automatic rate hikes. Estate planning can proceed with confidence that the first $15 million (or $30M for couples) of one’s wealth can pass to heirs tax-free, an opportunity for legacy planning. Business owners can invest and expand knowing key tax benefits (QBI, expensing) remain in place permanently. Investors and entrepreneurs can reap enhanced rewards via QSBS and other incentives, potentially building substantial wealth entirely tax-free if conditions are met. In short, the Act reinforces incentives to build, invest, and transfer wealth, which savvy planners will harness to their clients’ advantage.

Considerations and Caveats: Despite the label “One Big Beautiful Bill,” no legislation is perfect. The Act balloons the federal deficit by an estimated $1.7 to $2.9 trillion over a decade (dynamic basis) according to the Tax Foundation, chiefly by extending tax cuts. While this report doesn’t focus on debt, it’s relevant in that large deficits could necessitate future fiscal corrections such as potentially spending cuts or future tax increases. Individuals should be mindful that the political pendulum could swing: a different administration might attempt to scale back some of the opportunities (for example, by lowering the estate exemption or tweaking capital gains taxation). Planners should prepare for that possibility as flexibility in plans is key. For instance, using trusts that can adapt (via powers of appointment or decanting) if laws change, and considering moves like locking in low rates on conversions now, just in case rates rise later.

Another consideration is complexity. The Act, while simplifying in some respects (fewer expirations to worry about), also added new layers of rules (like the SALT phase-down, various temporary deductions, new acronyms for international taxes, etc.). Taxpayers and practitioners will need guidance on ambiguous areas. The IRS will be busy issuing regulations for the myriad changes – e.g., defining what jobs qualify for the tip deduction, how to implement the SALT phase-down, etc. This means some short-term uncertainty around implementation. For many, it underscores the importance of working with qualified professionals to navigate the new law’s provisions effectively and to minimize risk of mistakes.

Finally, it’s important to maintain a long-term perspective. Tax laws can and do change. The scheduled sunsets that prompted this bill are gone, but new sunsets or changes can appear with new legislation. Additionally, some OBBBA provisions themselves sunset (the SALT cap reset after TY 2029, the senior deduction and tip/overtime deductions after TY 2028). Clients will need reminders as those dates approach that certain benefits will lapse without further action by Congress. As of now, though, we have a relatively clear five-year horizon of rules and a favorable ten-year outlook for taxes.

In conclusion, the One Big Beautiful Bill Act profoundly impacts personal financial planning for all Americans. By understanding the Act’s provisions in depth as we have outlined in this report, Elyxium is prepared to help clients capitalize on the new opportunities (from mega estate exemptions to savvy SALT and trust strategies) and guard against potential downsides.

We encourage all to consult with their financial, tax, and legal advisors about how these changes apply to their specific situation. Sound planning today will ensure the capturing of the full benefits of this legislation while remaining prepared for how the future unfolds.

References:

Loeb & Loeb LLP. (2025, July 7). The One Big Beautiful Bill Act: Breaking Down Key Changes in the New Tax Legislation. (Client Alert/Report)

Sundvick, L. (2025, July 7). What You Need to Know About the One, Big, Beautiful Bill. Sundvick Legacy Center Blog.

Guberti, M. (2025, July 8). Here’s How Much Every Tax Bracket Would Gain — Or Lose — Under Trump’s “Big, Beautiful Bill”. GOBankingRates.

Nevius, A. M. (2025, July 7). Tax provisions in the One Big Beautiful Bill Act. Journal of Accountancy.

Sit, H. (2025, July 4). Social Security Is Still Taxed Under the New 2025 Trump Tax Law. The Finance Buff.

Todd N. Golper is a CERTIFIED FINANCIAL PLANNER™ CERTIFIED PRIVATE WEALTH ADVISOR™, Head of Strategy and Alternative Investments of Elyxium Wealth, LLC, a Registered Investment Adviser that offers comprehensive financial planning, retirement planning, and investment management.

The foregoing content reflects the opinions of Elyxium Wealth, LLC and is subject to change at any time without notice. Content provided herein is for informational purposes only and should not be used or construed as investment advice, financial advice, tax advice, or legal advice or a recommendation regarding the purchase or sale of any security. There is no guarantee that the statements, opinions, or forecasts provided herein will prove to be correct.

Each situation is unique. This information should not be constructed as formal financial advice, tax advice, or legal advice.

The above article was written with the assistance of artificial intelligence (AI).